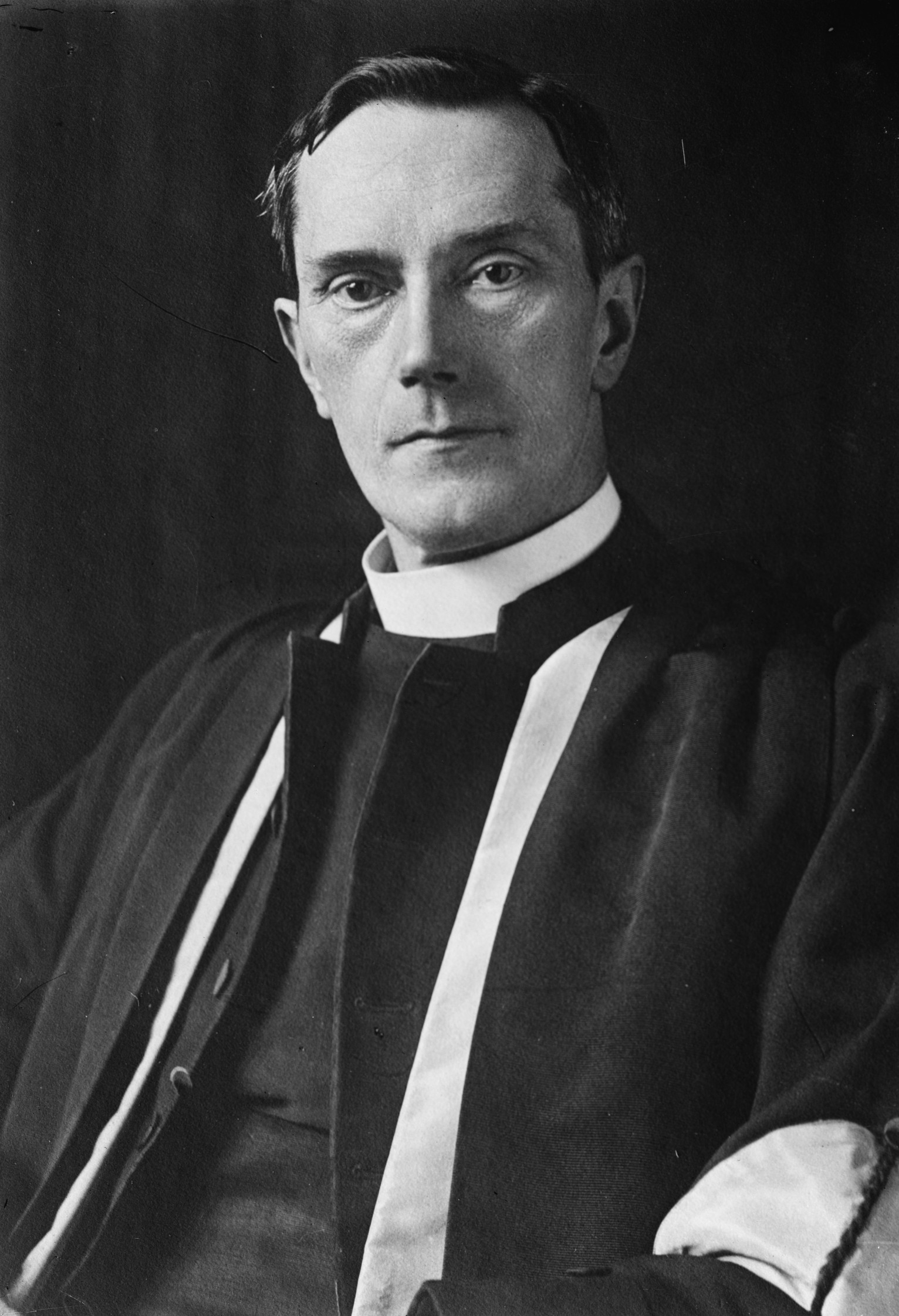

I have written often of W.R. Inge, the author of Christian Mysticism (1899) (linked on the sidebar), and of many other works, including Outspoken Essays (1920). Inge's great works on mysticism sets out certain stages that characterize the mystic path. A capsule version of this, from Outspoken Essays, sets the stage:

I have written often of W.R. Inge, the author of Christian Mysticism (1899) (linked on the sidebar), and of many other works, including Outspoken Essays (1920). Inge's great works on mysticism sets out certain stages that characterize the mystic path. A capsule version of this, from Outspoken Essays, sets the stage: Mysticism means an immediate communion, real or supposed, between the human soul and the Soul of the World or the Divine Spirit. The hypothesis on which it rests is that there is a real affinity between the individual soul and the great immanent Spirit, who in Christian theology is identified with the Logos-Christ. He was the instrument in creation, and through the Incarnation and the gift of the Holy Spirit, in which the Incarnation is continued, has entered into the most intimate relation with the inner life of the believer. This revived belief in the inspiration of the individual has immensely strengthened the position of Christian apologists, who find their old fortifications no longer tenable against the assaults of natural science and historical criticism. It has given to faith a new independence, and has vindicated for the spiritual life the right to stand on its own feet and rest on its own evidence. Spiritual things, we now realise, are spiritually discerned. The enlightened soul can see the invisible, and live its true life in the suprasensible sphere. The primary evidence for the truth of religion is religious experience, which in persons of religious genius—those whom the Church calls saints and prophets—includes a clear perception of an eternal world of truth, beauty, and goodness, surrounding us and penetrating us at every point. It is the unanimous testimony of these favoured spirits that the obstacles in the way of realising this transcendental world are purely subjective and to a large extent removable by the appropriate training and discipline. Nor is there any serious discrepancy among them either as to the nature of the vision which is the highest reward of human effort, or as to the course of preparation which makes us able to receive it. The Christian mystic must begin with the punctual and conscientious discharge of his duties to society; he must next purify his desires from all worldly and carnal lusts, for only the pure in heart can see God; and he may thus fit himself for 'illumination'—the stage in which the glory and beauty of the spiritual life, now clearly discerned, are themselves the motive of action and the incentive to contemplation; while the possibility of a yet more immediate and ineffable vision of the Godhead is not denied, even in this life.(From "Institutionalism and Mysticism," in Outspoken Essays).

These stages are called the Purgative Way, the Unitive Way, and the Illuminative Way, in Inge's more nuanced articulation in Christian Mysticism. The same three-fold path persists today; Christopher Bryant's superb 1980 work, The Heart in Pilgrimage uses the same tripartite division of the mystic path, as does Evelyn Underhill's exhaustive Mysticism (1910) (which graciously salutes Inge, who returns the compliment in later editions of Christian Mysticism). While Underhill examines the psychological dimension of the mystic quest, and Bryant deploys Jungian thinking (as well as sound spiritual guidance), Inge views it in terms of philosophy, finding, in later works, his "spriritual master" in the pagan philosopher Plotinus.

From Inge, as from Bryant and Underhill, can be found the source of the experience described as the sense of "sonship" by Henry Scott Holland: We know we are loved, because we experience love. The mystic path is not perforce one of self-denial for the sake of suffering, but rather the journey to the center to meet that love. That direct experience, as Inge postulates above, transcends the often sterile debate between doctrine and science, or between, I would add, sects. It is the experience that theologians strive to interpret, that creeds provide a structure for. It is the experience of being loved, and loving, of which St. Paul writes when he speaks of in Corinthians as the sine qua non of life in Christ.

For more Inge, see also his Light, Life and Love (1904).

No comments:

Post a Comment